10 Actions Schools Can Take Today to Increase Early Literacy Equity

In a recent survey conducted by Pearson of nearly 3,000 primary teachers, the top 3 challenges faced by students in 2021 were said to be: the widening of the disadvantage gap, focused intervention for individual students, and identifying gaps in learning.

Every school needs a plan to help all students achieve their full potential in the early years. Or students run the risk of not meeting literacy expectations throughout their schooling, which has been the case both before and after the pandemic.

Sprig has previously written on components of high-performing school improvement plans, focusing on particular case studies. It has also gleaned findings from over 30 case studies to provide guidance on improving early learning student achievement.

Those articles are strongly recommended for those who want to get a fuller understanding of how to raise early literacy scores.

Creating the right plan and formulating the right strategy are important, but sometimes it helps to review ready-made actionable recommendations to help those students who are in dire need.

What are some things schools can do today to boost reading proficiency scores and accelerate both learning gains and learning recovery? These 10 actions can be implemented by any school to increase literacy equity.

10 Actions That Promote Literacy Equity

1. Develop and Communicate Goals Around Early Literacy

There are many examples of school districts establishing specific literacy goals for students by the end of Grade 3. It helps to have such goals in place, which sets forth the vision of what is to be achieved. Top-down accountability considers the academic wellbeing of every student.

For example, in Las Vegas, Nevada, Clark County School District Superintendent, Jesus Jara, has a goal of increasing Grade 3 reading scores by 7 percentage points.

2. Identify a Reading Curriculum That Is Suited to Achieving Your Goals

Identifying the right reading curriculum (or program) that aligns to the research and evidence around the Science of Reading is essential for early literacy success. This must also align to the school’s vision, philosophy and learning objectives for early literacy success.

An evidence-based reading curriculum is so important because it helps in both horizontal and vertical planning. Teachers must plan for the school year. They must also know what the learning expectations are for students at both the beginning and end of the school year. In this way, the early learning journey of every young student is accounted for.

3. Adopt a Early Literacy Screen to Identify Student Needs

Every state and province across North America has Grade 3 or Grade 4 standardized assessment. But there are 12 states in the US that don’t have mandated kindergarten entrance assessments. In Canada, there are no mandated kindergarten entrance assessments as of now.

If student performance will be measured at Grade 3, it also makes sense to measure a baseline. It does not necessarily have to be standardized, but can be adopted and customized by individual schools to understand how to best help each student. Sprig Language, for example, offers such an initial assessment screen that uncovers each student’s strengths, needs and interests in regards to oral language.

4. Scaffold Individual Grade 2 Learners to Proficiency

By Grade 2, emerging readers should have acquired phonological awareness and phonics skills that will enable them to stay at grade level. But at times when there has been so much disruption to learning, there are many students who still struggle with these skills, for whom scaffolding may be required.

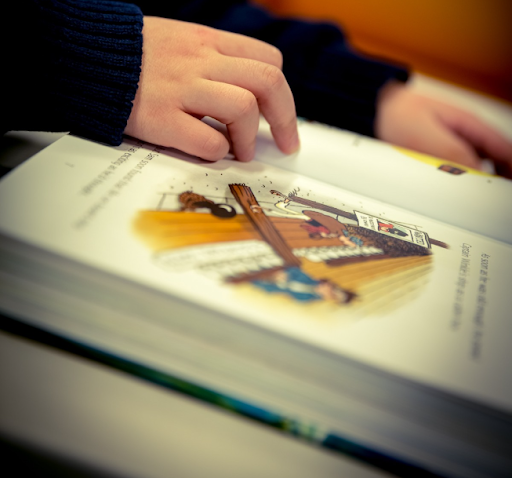

Given that the Pre-K to 3 period is so crucial, assumptions of proficiency must not be made. It’s important to have regular formative assessments that monitor the growth of every student’s ability to read.

5. Adopt a School-Wide Literacy Plan

Literacy skills do not have to be restricted to language classes. Reading skills can be included in other subjects as well, such as math and science. Administrators can provide guidance to all teachers in figuring out how to incorporate certain evidence-based literacy skills into their lesson plans.

In Cedar Valley Community School in Washington, literacy intervention specialist Kim Copeland, has expanded the school’s literacy program where students can practice the literacy skills they need throughout the day, and in general education classrooms.

6. Set High Standards

In order to achieve literacy equity, expectations should be realistic. But they should also be ambitious to realize the highest latent potential for success for every child.

The Leave No Child Behind report from UNESCO, says that principals in schools where the students succeed have a can-do attitude. In all the most improved schools cirted in the report, high expectations are set, where a consistent, coherent and focused literacy program is applied.

7. Identify Struggling Readers as Early as Possible

Time is of the essence in early literacy success. Whether it’s finding out if someone has dyslexia, or finding out if certain circumstances are preventing a student from gaining an optimum learning experience, such information needs to be known early on, so the right countermeasures can be taken.

Not every state in the US has mandated dyslexia screening. But that does not mean an individual school cannot offer this screening service to its students. Early literacy intervention is a point that cannot be stressed enough.

8. Establish a Multi-tiered System of Support

A multi-tiered system of support is a framework that aims to improve learning outcomes for all students, depending on the type of support required. A school should have a common shared language to identify students according to their level of needs.

The highest-quality evidence-based instruction should be provided to the whole classroom. But for those students who need extra support via small group instruction, such help should be made available to them.

9. Hire Positions Specializing in Literacy

It’s important to provide primary teachers the help they need to teach early literacy to all students. Literacy coaches, reading specialists, literacy interventionists, and literacy coordinators make a big difference in the quality of the early learning experience. The efficiency of such positions have been repeatedly proven.

Fulton County Schools adopted the Every Child Reads Plan in 2021, which includes placing designated reading coaches and paraprofessionals in every elementary school in the district.

10. Establish Collective Ownership of Literacy Goals

When hiring new positions and fostering a culture of early literacy success, it is important to obtain buy-in from all teachers, staff and administrators.

Rollie O. Jones, principal at Kellman Corporate Community School in Chicago, says “we have a cross-section of teachers, some young, some seasoned, some in-between, but they all must buy into our vision. I look for teachers who will make that commitment to a coordinated curriculum and become part of our family here in the school.”

Programs VS Practices in Early Literacy Equity

Efforts to find the best early literacy programs usually revolve around the teaching resources used by educators. There are so many resources available and new ones are being created every school year. The findings of the effectiveness of all such programs have been discrepant.

Rather, studies that focus on best practices have yielded more consistent results over the years. It is difficult to determine one best program that is superior to all others for achieving literacy equity. But it is possible to determine best practices based on evidence that shows robust relationships between particular practices and high literacy achievement.

This article showcased 10 such practices, at both a teacher and administrator level, which when applied can lead to successful outcomes for all students.

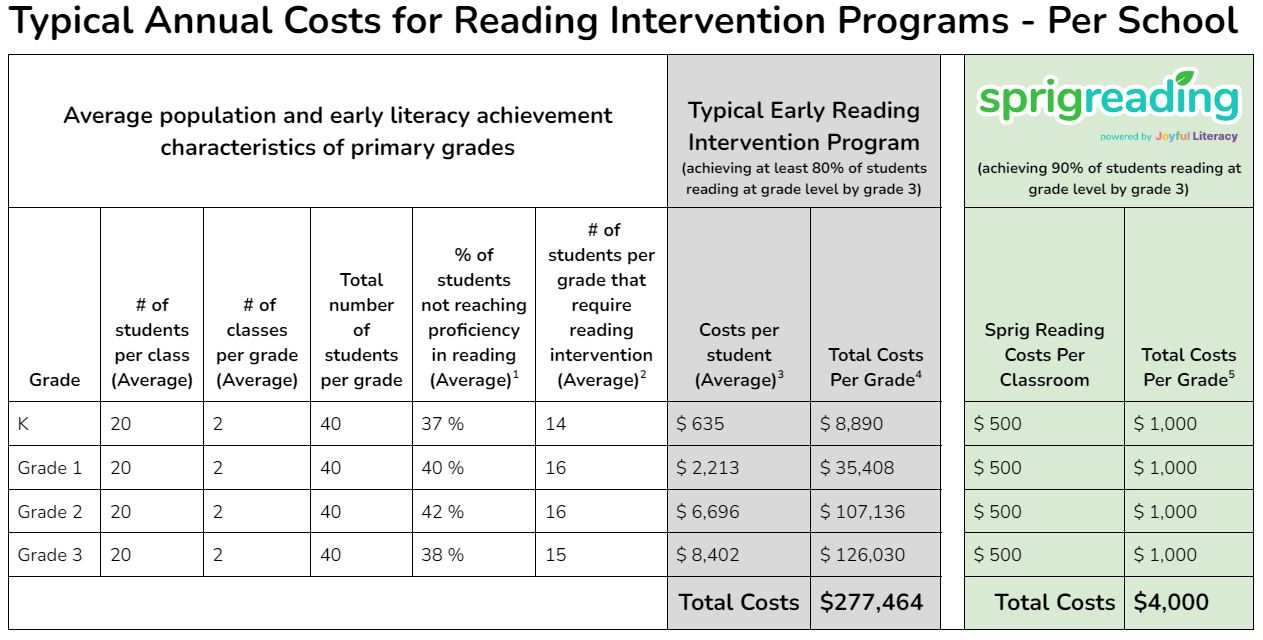

Sprig Reading, Sprig Learning’s newest early learning platform, is an interactive tool for evidence-based instruction. It promotes teaching, assessment and differentiation best practices in early reading, so teachers have a way to teach the foundational skills and concepts, and track the progression of students.